The Lore of the Lyrebird (2014). Video and a collection of wood engravings. Display: ‘MetaMètode 2014′, group exhibition at Centro Cultural El Carme of Badalona, Barcelona, from September 4 to October 10, 2014. Publication: ‘Metamétodo. Shared Methodologies in Artistic Processes’. 2014, Pages 34-41, ISBN 978-84-16033-27-0. Research project ‘Metamethod: Shared Methodologies and Artistic Processes in the Society of Knowledge’. 2011-2013. HAR2010-18453 (subprogram ART). Funded by The Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, co-financed with European Funds.

The Lore of the Lyrebird

My artistic proposal stems from a quotation of William Ivins, written during the Second World War: “The graphic processes and techniques have grown and developed to the end of conveying information. The illustration that has contained the greatest amount of information, i.e., of detail, has been the one that was most in demand. As a result of this the graphic processes have shown an ever increasing fineness of texture. This increasing fineness of texture has repeatedly been carried to the point where the current process was no longer economically practicable, and then there has been a shift over to some other process that while producing approximately a similar result has been economically more advantageous”[1]. The theory of print fits in with a notion of evolutionary progress. However, technological progress doesn’t correspond to social progress. In the context of printmaking this means that detail is not synonymous with information and in a broader context signifies annihilation. For Ivins the invention of printing was comparable to that of writing; the exact repetition of images determined the development of science and technology, with the artistic value of a print becoming something secondary[2]. His Prints and Visual Communication, of 1953, could equally have been titled Art and science, given that it deals with the tension between the artistic and scientific value of the mechanically reproduced image.

The male lyrebird, to court the female, is capable of imitating a wide variety of sounds. It is capable of reproducing the song of at least 20 species of bird, even managing to dupe the original. It can also copy the sound of a photographic camera, a car alarm, a saw, a hammer, etc. This information appears repeatedly in the wide variety of videos of the lyrebird that I’ve compiled from YouTube, be they documentaries about their life in the wild, on the news on television or in propaganda for a zoo. I’ve made a little collage out these videos. The first fragment, that has been reproduced 11.895.003 times on YouTube, belongs to the series The Life of Birds by David Attenborough, on the BBC, from the year 1998. The last part of my video-collage, in which the bird appears in a cage, has been reproduced only 1.665.603 times and was uploaded by The Royal Zoological Society of South Australia (RZSSA) in August 2009. From the video-collage emerges the following suspicion; that either the same lyrebird is reproduced, or in reality it has a fairly limited repertoire. The lyrebird compulsively imitates the sound of film cameras, but can’t manage to learn the many, subtle sounds of digital cameras.

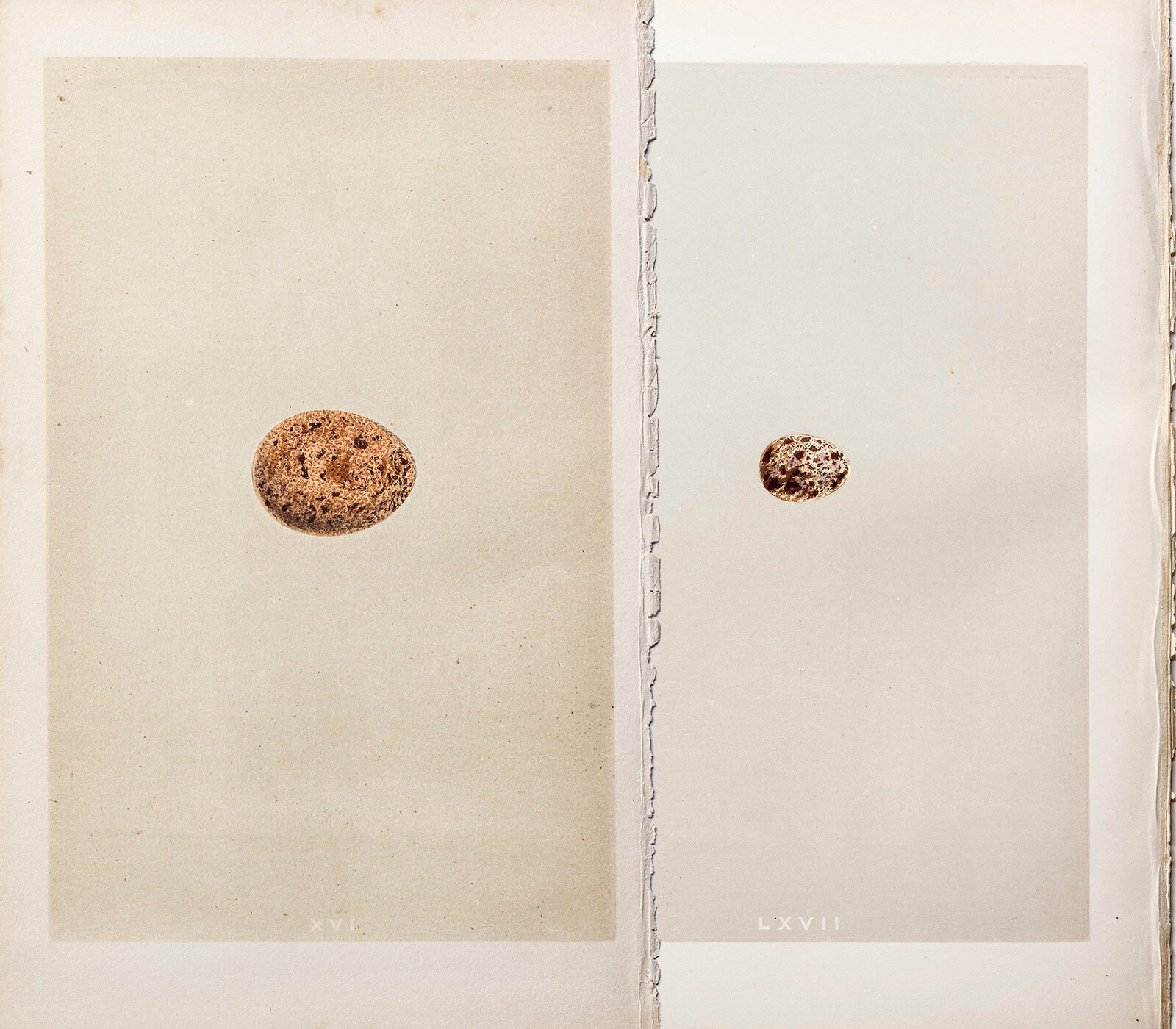

I’m also showing a small collection of prints of eggs that I bought on Ebay, pages pulled out of a book on ornithology, published in 1853 six years before Darwin’s Origin of the Species. Benjamin Fawcett was the printer and editor of the eggs, adapting Bewick’s wood engravings to colour printing. These colour prints are on the cusp of technological development, one of those very extremes where finesse becomes economically unviable. Fawcett had to print several woodblocks on the same page in order to differentiate the splodges of each egg. The shadows have been painted by hand, that is to say, they’ve been hand illuminated. The eggs appear floating on a grey background that frames the image in a manner analogous to artists’ prints of the 20th C, with less space on each side and a larger space on the lower margin. The adroitness is amazing. The visual intelligence of the printer consists in developing graphic ideas so that they pass unnoticed. In print a lot of necessary information is eliminated, such as the registration marks or colour references. What is amazing is that the eggs seem credible. The prints of the nests aren’t and I won’t be showing them. In the nests one intuits the register, as well as the drawing and a choice of colours that has no pretensions of being realistic.

If the artist has to make his intelligence expressive, the repetitions of the Laocoon in the illus – trations of Ivins in 1953 perhaps anticipate Andy Warhol’s repetitions of Campbell’s chicken soup, in 1962. But Ivins wasn’t an artist; as the print curator for an art museum, the Metropolitan in New York, he was interested in the scientific value of the prints. He also wasn’t able to foresee the artistic worth that the photo-etchings of John Heartfield would have today, nor their documentary value. They didn’t however pass unnoticed by Walter Benjamin. The document is very expressive: he warns us of the war and talks about destruction converted into natural science.

Nobody remembers Benjamin Fawcett, unlike Bewick he doesn’t appear as an author. The quotation that serves to set this project in motion applies to a wood engraving that imitates the burin, translating Bewick into Fawcett, but this becomes problematic. It’s worth remembering that lithography, which already permitted direct drawing with no need for etching was invented during the same period as Bewick. Bewick’s invention was conservative, but it conjoined his passions: drawing, engraving and ornithology. These required the coordination of production and distribution. His virtuosity is due to the necessary lift of associating himself with his master’s, Ralph Beilby’s, business. The craftsman’s passion made possible the ornithologist’s enjoyment of copying and classifying stuffed birds without having to submit to the tedious craft of copying prints. Fawcett’s passions were more discrete they materialize in the splodges on the eggs. Lithography arises out of a fantasy: Aloys Senefelder invented a completely new procedure in the hope of triumphing as a playwright. Wood engraving proliferated in the press of the 19thC, and scientific publications of the era resemble illustrated magazines. The romantic novel owes its best illustrations to it. The first illustrated newspaper, Le Charivari, owes its central page to lithography, that of the caricatures of Honoré Daumier, so valuable for Heartfield.

The social sciences crystallize in the natural sciences. Art coolly expresses a subjectivity that in the sciences is passionately annulled. The eggs of Fawcett might not fool a bird. But what do the eggs of the lyrebird look like, where do they appear represented? At the beginning of 1953 Elias Canetti gave to Iris Murdoch a book about the lyrebird; they later became lovers. At the end of 2011 a bird called Chook appeared in the obituaries in the press; he had become a star on YouTube and died on 29 December in 2011, at 32 years of age. In the book, that Canetti gave, a lyrebird courted a woman who lives in the jungle. Thanks to this one discovers for the first time the customs of the alienated bird. The book begins like this: “One of the most beautiful and rare and certainly the most intelligent of all the world’s wild creatures is that incomparable artist, the Lyrebird”[3]. The project that I present combines two elements: the eggs of the printer and the exhibitionistic bird. Would you like to come up and see my etchings?

[1] William Ivins, How Prints Look (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1943) p. 144.

[2] William Ivins, Prints and Visual Communication (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1953) p. 2.

[3] Ambrose Pratt, The Lore of the Lyrebird (Sydney: The Endeavour Press, 1933) p. 15.

The video is a collage obtained from the following links (access 12/11/2013):

Amazing! Bird sounds from the lyre bird – David Attenborough – BBC wildlife. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjE0Kdfos4Y Uploaded by BBCWorldwide on 12/02/2007. 11.916.021 views.

World’s Weirdest: Bird Mimics Chainsaw, Car Alarm and More. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XjAcyTXRunY Uploaded by NatGeoWild on 18/04/2012. 333.499 views.

Very funny bird “lyre” can copy any sound it hears. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckRmUEK9E1A&feature=related Uploaded by mr2000jp on 11/07/2010. 7.756 views.

Chook the Lyrebird. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gn6LimmBui8 Uploaded by Phobosuchus1 on 27/03/2011. 56.695 views.

The Lyrebird 2.avi. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xr-o7Cw9zA0&feature=related Uploaded by ronieliav on 04/04/2010. 132.293 views.

Superb Lyrebird imitating construction work Adelaide Zoo. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeQjkQpeJwY Uploaded by The Royal Zoological Society of South Australia (RZSSA) on 03/08/2009. 1.667.980 views.

The eggs appeared in 3 volumes: F. O. Morris, A Natural History of the Nests and Eggs of British Birds. London: Goombridge, 1853-1856. I found on Amazon a first edition probably published in installments, as it gathers fragments of the first two volumes bound into a single book. The Ebay prints are 22 sheets torn probably from a later reprint, the colors do not match those of the book and the paper is slightly more glossy. A copy of the last edition of the Eggs, from 1896, can be downloaded from Internet Archive, but it has little to do with Fawcett, it was printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.